Table of Contents

A single-threaded event loop like the one used by JavaScript and Node.js, makes it somewhat harder to have race conditions, but, SPOILER ALERT: race conditions are still possible!

In this article, we will explore the topic of race conditions in Node.js. We will discuss some examples and present a few different solutions that can help us to make our code race condition free.

What is a race condition?

First of all, let’s try to clarify what a race condition actually is.

A race condition is a type of programming error that can occur when multiple processes or threads are accessing the same shared resource, for instance, a file on a file system or a record in a database, and at least one of them is trying to modify the resource.

Let’s try to present an example. Imagine that while a thread is trying to rename a file, another thread is trying to delete the same file. In this case, the second thread will receive an error because, when it’s trying to delete the file, the file has already been renamed. Or, the other way around, while one thread is trying to rename the file, the file was already deleted by the other thread and it’s not available on the filesystem anymore.

In other cases, race conditions can be more subtle, because they wouldn’t result in the program crashing, but they might just be the source of an incorrect or inconsistent behaviour. In these cases, since there is no explicit error and no stack trace, the issue is generally much harder to troubleshoot and fix.

A classic example is when 2 threads are trying to update the same data source and the new information is the result of a function applied to the current value.

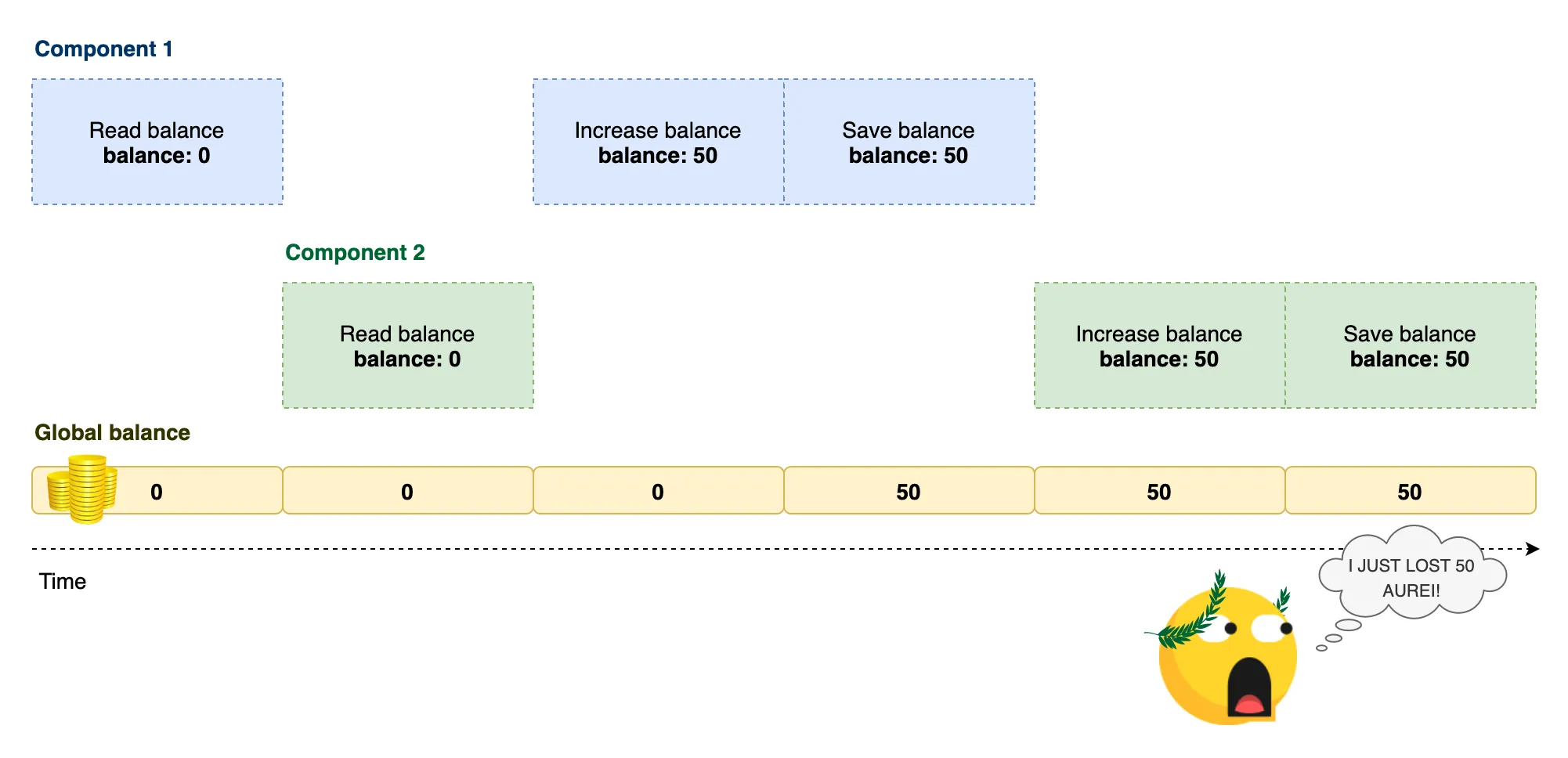

Let’s pretend we are building a Roman Empire simulation game in which we can manage some cash flow and we have a global balance in aureus (a currency used in the Roman Empire around 100 B.C.E.). Now, let’s say that our initial balance is 0 aurei and that there are two independent game components (possibly running on separate threads) that are trying to increase the balance by 50 aurei each, we should expect that in the end, the balance is 100 aurei, right?

0 + 50 + 50 = 100 🤑If we implement this in a naive way, we might have the two components performing three distinct operations each:

- Read the current value for

balance - Add

50aurei to it - Save the resulting value into

balance

Since the two components are running in parallel, without any synchronisation mechanism, the following case could happen:

In the picture above you can see that Component 2 ends up having a stale view of the balance: the balance gets changed by Component 1 after Component 2 has read the balance. For this reason, when Component 2 performs its own update, it is effectively overriding any change previously made by Component 1. This is why we have a race condition: the two components are effectively racing to complete their own tasks and they might end up stepping onto each other’s toes! This doesn’t make Julius happy I am afraid…

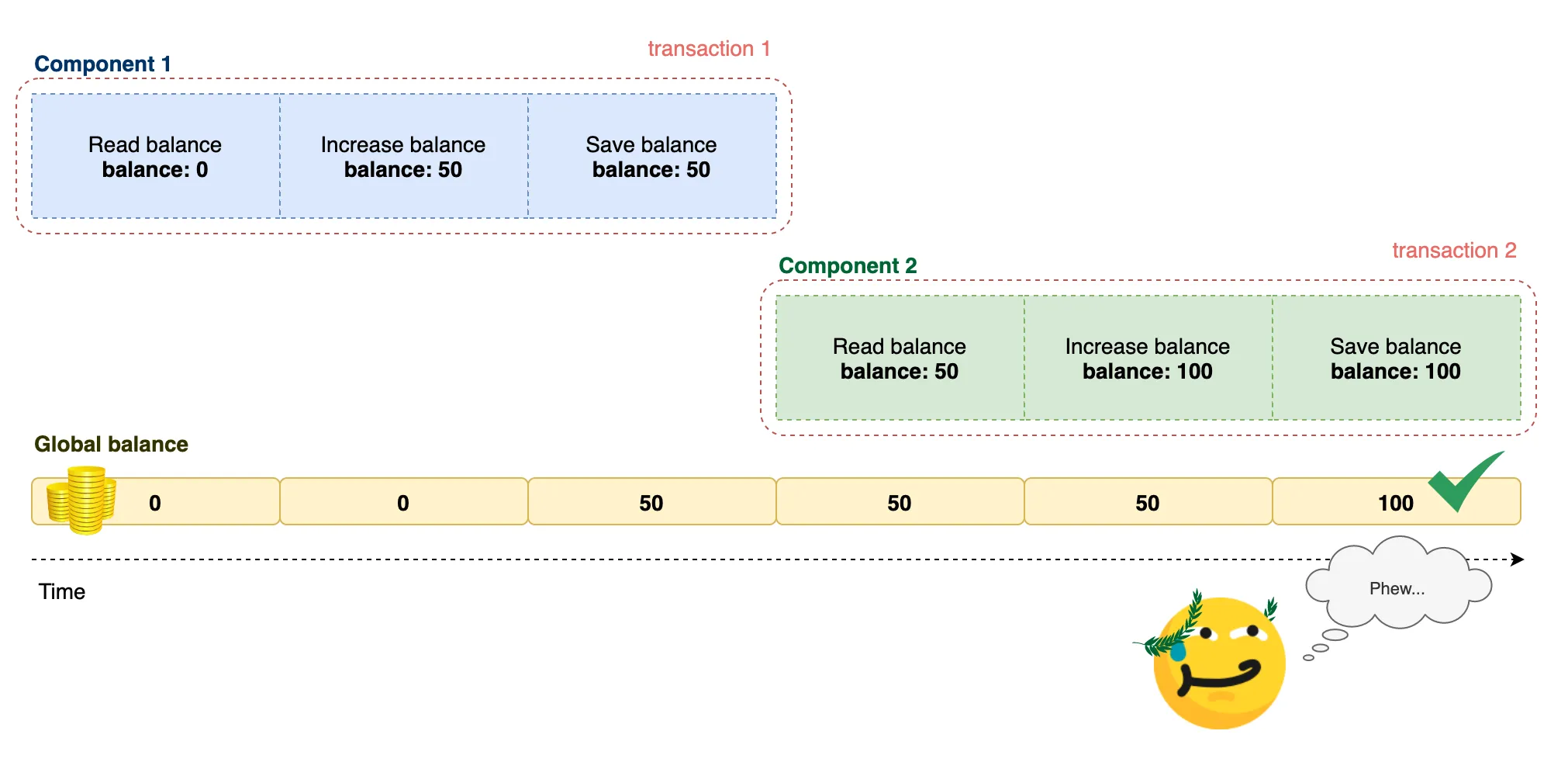

One way to solve this problem is to isolate the 2 concurrent operations into transactions and make sure that there is only one transaction running at a given time. This idea might look like this:

In the last picture, we are using transactions to make sure that all the steps of Component 1 happen in order before all the steps of Component 2. This prevents any stale read and makes sure that every component always has an up to date view of the world before doing any change. You can stop holding your breath now, Julius!

In the rest of this article, we will zoom in more on race conditions in the context of Node.js and we will see some other approaches to deal with them.

Can we have race conditions in Node.js?

It is a common misconception to think that Node.js does not have race conditions because of its single-threaded nature. While it is true that in Node.js you would not have multiple threads competing for resources, you might still end up with tasks belonging to different logical transactions being executed in an order that might result in stale reads and generate a race condition.

In the example that we illustrated above, we intentionally represented the various tasks (read, increase and save) as discrete units. Note how the system is never executing more than one task at the same time. This is a simple but accurate representation of how the Node.js event loop processes tasks on a single thread. Nonetheless, you can see that there might be situations where multiple logical transactions (e.g. multiple deposits) are scheduled concurrently on the event loop and the discrete tasks might end up being intermingled, which results in a race condition.

So… Yes, we can have race conditions in Node.js!

A Node.js example with a race condition

Now, let’s talk some code! Let’s try to re-create the Roman Empire simulation game example that we discussed above.

In ancient Rome, Romans used to export olives and grapes. No wonder Italy is still famous worldwide for olive oil and wine! In our game, we want to be able to harvest olives and grapes and then sell them as a means to acquire more aurei.

We are going to have two functions that can increase the balance by 50 aurei which we are going to call sellOlives() and sellGrapes(). We will also assume that every time the balance is changed, it is persisted to a data storage of sort (e.g. a database). For the sake of this example, we won’t be using a real data storage, but we will just simulate some random asynchronous delay before reading or modifying a global value. This will be enough to illustrate how we can end up with a race condition.

For starts, let’s see what a buggy implementation might look like:

// Utility function to simulate some delay (e.g. reading from or writing to a database).// It will take from 0 to 50ms in a random fashion.const randomDelay = () => new Promise((resolve) => setTimeout(resolve, Math.random() * 100))

// Our global balance.// In a more complete implementation, this will live in the persistent data storage.let balance = 0

async function loadBalance() { // simulates random delay to retrieve data from data storage await randomDelay() return balance}

async function saveBalance(value) { // simulates random delay to write the data to the data storage await randomDelay() balance = value}

async function sellGrapes() { const balance = await loadBalance() console.log(`sellGrapes - balance loaded: ${balance}`) const newBalance = balance + 50 await saveBalance(newBalance) console.log(`sellGrapes - balance updated: ${newBalance}`)}

async function sellOlives() { const balance = await loadBalance() console.log(`sellOlives - balance loaded: ${balance}`) const newBalance = balance + 50 await saveBalance(newBalance) console.log(`sellOlives - balance updated: ${newBalance}`)}

async function main() { const transaction1 = sellGrapes() // NOTE: no `await` const transaction2 = sellOlives() // NOTE: no `await` await transaction1 // NOTE: awaiting here does not stop `transaction2` // from being scheduled before transaction 1 is completed await transaction2 const balance = await loadBalance() console.log(`Final balance: ${balance}`)}

main()If we execute this code we might end up with different results. In one case we might get the correct outcome:

sellOlives - balance loaded: 0sellOlives - balance updated: 50sellGrapes - balance loaded: 50sellGrapes - balance updated: 100Final balance: 100But in other cases we might end up in a bad state:

sellGrapes - balance loaded: 0sellOlives - balance loaded: 0sellGrapes - balance updated: 50sellOlives - balance updated: 50Final balance: 50Note how in this last case, sellOlives is essentially a stale read and therefore it will end up overriding the balance disregarding any work already done by sellGrapes. Yes, we do have a race condition, unfortunately!

Now, this example is simple ad it is not too hard to pinpoint exactly where the race condition has originated by just looking at the code.

Take a minute or two to read the code again. Check out the output from the 2 cases as well. Pay attention to the notes and the log messages and try to imagine how the Node.js runtime might execute this code in the 2 different scenarios.

Ok, now that you have done that, let’s discuss together what happens.

In our main function, when we execute sellGrapes() and sellOlives(), since we are not awaiting the two operations independently, we are essentially scheduling both operations onto the event loop.

We only await the two transactions after they have been already scheduled, which means that they will work concurrently. After the two transactions have been scheduled, we wait for transaction1 to complete and only then we wait for transaction2 to complete. Note that transaction2 might complete even before transaction1. In other words, awaiting for transaction1 doesn’t block transaction2 in any way.

This approach is similar to writing the following code:

await Promise.all([sellGrapes(), sellOlives()])Using Promise.all() is a more commonly used way to schedule different tasks to run concurrently. If you want to learn more about JavaScript async patterns including async iterators, check out our article on JavaScript async iterators.

Note that with Promise.all(), the resulting promise will reject as soon as any of the promises rejects. In our previous example, since we await the two promises independently, we will always catch errors in transaction1 before transaction2.

But let’s not digress too much into this. Now that we understand the problem, how do we fix the race condition?

Well, it turns out that in this simple case, we might make things right quite easily:

async function main() { await sellGrapes() // <- schedule the first transaction and wait for completion await sellOlives() // <- when it's completed, we start the second transaction // and wait for completion const balance = await loadBalance() console.log(`Final balance: ${balance}`)}This implementation will consistently produce the following output:

sellGrapes - balance loaded: 0sellGrapes - balance updated: 50sellOlives - balance loaded: 50sellOlives - balance updated: 100Final balance: 100As we can observe, sellGrapes is always started and completed before we start sellOlives. This makes the two logical transactions isolated and makes sure their tasks won’t end up being mixed together in random order.

Problem solved… vade in pacem dear race condition!

Using a mutex in Node.js

OK, the previous example was illustrative, but if we are building a real game, chances are things will end up being a lot more complicated. We will probably end up having many different actions that might cause a change of balance. Those actions might be the result of a particular sequence of events and it might become hard to track down the discrete logical transactions that we have to serialize in order to avoid race conditions.

Ideally, we don’t want to think in terms of transactions, we just need to make sure that we never read the balance if there is another concurrent operation that is ready to change its value.

To be able to do this we need two things:

- Have a way to identify when we are about to change the balance

- Let other events wait in line until the change is completed before reading the balance

We could say that when we are about to change the balance we enter a critical path and that we don’t want to intermingle events from different logical transactions in a critical path.

One way to achieve this is by using a Mutex (which stands for mutual exclusion).

A mutex is a mechanism that allows synchronising access to a shared resource.

We can see a mutex as a shared object that allows us to mark when the code execution is entering and exiting from a critical path. In addition to that, a mutex can help us to queue other logical transactions that want to access the same critical path while one transaction is being processed.

Before talking code, be aware that using a mutex might have a performance impact in your application and that this solution won’t work if you use a distributed or a multi-process setup. More details on this later.

Using async-mutex

A very useful library that we can useg is async-mutex. This library provides a promise-based implementation of the mutex pattern.

You can install this library from npm:

npm install --save async-mutexNow, here’s an example of how we could use this library to mark the beginning and the end of a critical path:

import { Mutex } from 'async-mutex'

const mutex = new Mutex() // creates a shared mutex instance

async function doingSomethingCritical() { const release = await mutex.acquire() // acquires access to the critical path try { // ... do stuff on the critical path } finally { release() // completes the work on the critical path }}In this example, we are using a global mutex instance to mark the beginning and the end of a critical path which happens inside our doingSomethingCritical() function.

When we call mutex.acquire(), this method will return a promise. If no other concurrent operation is currently on the same critical path, the promise resolves to a function that we call release. In this situation, we are essentially granted exclusive access to the critical path. If some concurrent operation is on the critical path already, the promise won’t resolve until the concurrent operation already on the critical path has completed. This is how concurrent operations wait in line for our exclusive access to the critical path.

The release function must be invoked to mark the completion of the work on the critical path. It effectively releases the exclusive access to the critical path and makes it available to the next task in line. Note that we are using a try/finally block here to make sure that release is called even in case of an exception. It is very important to do so. In fact, failing to call release, will leave all the other events waiting in line forever!

Now let’s try to use async-mutex to avoid race conditions in our game:

import { Mutex } from 'async-mutex'

const randomDelay = () => { /* ... */}

let balance = 0const mutex = new Mutex() // global mutex instance

async function loadBalance() { /* ... */}async function saveBalance(value) { /* ... */}

async function sellGrapes() { // this code will need exclusive access to the balance // so we consider this to be a critical path const release = await mutex.acquire() // get access to the critical path (or wait in line) try { const balance = await loadBalance() console.log(`sellGrapes - balance loaded: ${balance}`) const newBalance = balance + 50 await saveBalance(newBalance) console.log(`sellGrapes - balance updated: ${newBalance}`) } finally { release() // completes work on the critical path }}

async function sellOlives() { // similar to `sellGrapes` this is a critical path because // it needs exclusive access to balance const release = await mutex.acquire() try { const balance = await loadBalance() console.log(`sellOlives - balance loaded: ${balance}`) const newBalance = balance + 50 await saveBalance(newBalance) console.log(`sellOlives - balance updated: ${newBalance}`) } finally { release() }}

async function main() { // Here we can call many events safely, the mutex will guarantee that the // competing events are executed in the right order! await Promise.all([ sellGrapes(), sellOlives(), sellGrapes(), sellOlives(), sellGrapes(), sellOlives(), ]) const balance = await loadBalance() console.log(`Final balance: ${balance}`)}

main()The code above will consistently produce the following output:

sellGrapes - balance loaded: 0sellGrapes - balance updated: 50sellOlives - balance loaded: 50sellOlives - balance updated: 100sellGrapes - balance loaded: 100sellGrapes - balance updated: 150sellOlives - balance loaded: 150sellOlives - balance updated: 200sellGrapes - balance loaded: 200sellGrapes - balance updated: 250sellOlives - balance loaded: 250sellOlives - balance updated: 300Final balance: 300Some of the code has been truncated for simplicity. You can find all the examples in this repository.

From the example above, you can see how mutexes can provide a convenient way of thinking about exclusive access and how they can help to avoid race conditions. We are intentionally triggering multiple calls to sellGrapes() and sellOlives() concurrently, to make obvious that we don’t have to think about potential race conditions at the calling point. This means that, as our game grows more complicated, we can keep invoking these functions without having to worry about generating new race conditions.

Let’s implement a mutex

But what if we are dealing with a race condition only in one place in our entire application? Is it worth to include and manage an external dependecy just because of that? Can we come up with a simpler alternative that does not require us to install a new dependency?

It turns out that we can easily do that! Let’s see how we can implement our own mutex.

Note that the solution we are going to present here is effectively a variation of the sequential execution pattern using promises that is presented in Chapter 5 of Node.js Design Patterns.

The idea is to inizialize our global mutex as an instance of a resolved promise:

let mutex = Promise.resolve()Then in our critical path we can do something like this:

async function doingSomethingCritical() { mutex = mutex .then(() => { // ... do stuff on the critical path }) .catch(() => { // ... manage errors on the critical path }) return mutex}The idea is that every time we are invoking the function doingSomethingCritical() we are effectively “queueing” the execution of the code on the critical path using mutex.then(). If this is the first call, our initial instance of the mutex promise is a resolved promise, so the code on the critical path will be executed straight away on the next cycle of the event loop.

Calling .then() on a promise returns a new promise instance that is used to replace the original mutex instance and it’s also returned by the doingSomethingCritical() function.

This allows us to have concurrent calls to doingSomethingCritical() being queued to be executed sequentially.

Note that we also specify a mutex.catch(). This allows us to catch and react to specific errors, but it also allows us not to break the chain of sequential execution in case an operation fails.

Ok, now that we have explored this idea, let’s apply it to our example.

This is how our code is going to look like:

const randomDelay = () => { /* ... */}

let balance = 0let mutex = Promise.resolve() // global mutex instance

async function loadBalance() { /* ... */}async function saveBalance(value) { /* ... */}

async function sellGrapes() { mutex = mutex .then(async () => { const balance = await loadBalance() console.log(`sellGrapes - balance loaded: ${balance}`) const newBalance = balance + 50 await saveBalance(newBalance) console.log(`sellGrapes - balance updated: ${newBalance}`) }) .catch(() => {}) return mutex}

async function sellOlives() { mutex = mutex .then(async () => { const balance = await loadBalance() console.log(`sellOlives - balance loaded: ${balance}`) const newBalance = balance + 50 await saveBalance(newBalance) console.log(`sellOlives - balance updated: ${newBalance}`) }) .catch(() => {}) return mutex}

async function main() { await Promise.all([ sellGrapes(), sellOlives(), sellGrapes(), sellOlives(), sellGrapes(), sellOlives(), ]) const balance = await loadBalance() console.log(`Final balance: ${balance}`)}

main()If you try to run this code, you will see that it consistently prints the same output as per our previous implementation using async-mutex!

So, here we have it, a simple mutex implementation in just few lines of code leveraging promise chainability!

Mutex with multiple processes

It is important to mention that the solutions presented in this article only work in a Node.js application running on a single process.

If you are running your application on multiple processes (for instance, by using the cluster module, worker threads or a multi-process runner like pm2) using a mutex within our code is not going to solve race conditions across processes. This is also the case if you are running your application on multiple servers.

In these cases you have to rely on more complicated solutions like distributed locks or, if you are using a central database, you can rely on solutions provided by your own database systems. We will discuss a simple example in the next section.

Mutex performance

We already mentioned that using a mutex might have a relevant performance impact in your application.

To try to visualize why a mutex has a performance impact in your application let’s try to think about the case when an operation is trying to acquire a lock on a mutex but the mutex is already locked. In this case, our operation is simply waiting without doing nothing, while for instance it could be doing some IO operation like connecting to the database or sending a query. It will probably take the event loop several spins before the lock is released and the operation that is waiting in line can acquire the lock. This get worse with a high number of operations waiting in line.

With a mutex we are effectively serializing tasks, making sure that executed in sequence and non-concurrently. If you abuse this pattern, you might end up in a situation where you could effectively eliminate all concurrency from your application.

Measuring how a mutex might impact your specific application is not something that can be done holistically and we recommend you to run your own benchmarks to find out what is the effect of introducing one or more mutex instances in your application.

Our general recommendation is to use a mutex only when you are sure you have to protect your code from a race condition and to try to make the critical path as short as possible.

Be aware that a mutex is not the only solution to race conditions. For instance, in our example, if we were to use a real relational database as a data storage, we could have avoided any race condition (at the application level) by letting the database itself do the increment using a SQL query:

UPDATE game SET aurei = aurei + 50;With this approach, we are trusting the database to do the right thing and we are not slowing down our application.

And there are other alternative approches. Just to name one, optimistic locks might provide a great alternative if race conditions are possible but they actually happen only in rare occasions.

Conclusion

In this article, we have explored race conditions and learned why they can be harmful. We showed how race conditions can happen in Node.js and several techniques to address them including the adoptopm of a mutex.

This is an interesting topic which often gets explored in the context of multi-threaded languages. The theory isn’t much different but there are some important differences when dealing with concurrent, single-threaded languages like Node.js.

If you are curious to understand better the difference between Parallelism and Concurrency I strongly recommend you to read this great essay titled parallelism and concurrency need different tools. You can also watch this wonderful talk by Steve Klabnik called Rust’s Journey to Async/Await (yes, it’s not only about Rust, trust me).

I really hope you enjoyed this article. Make sure to reach out to me on Twitter and let me know what you think!

Bye 😋

Credits

Thanks to Jack Barry for the inspiration for this post on the Node.js Design Patterns discussion board. Thanks to Peter Caulfield, Stefano Abalsamo, Roberto Gambuzzi and Mario Casciaro for kindly reviewing this post.